Seeing the Invisible: The First North American Electron Microscope

Written by Anastassia Pogoutse

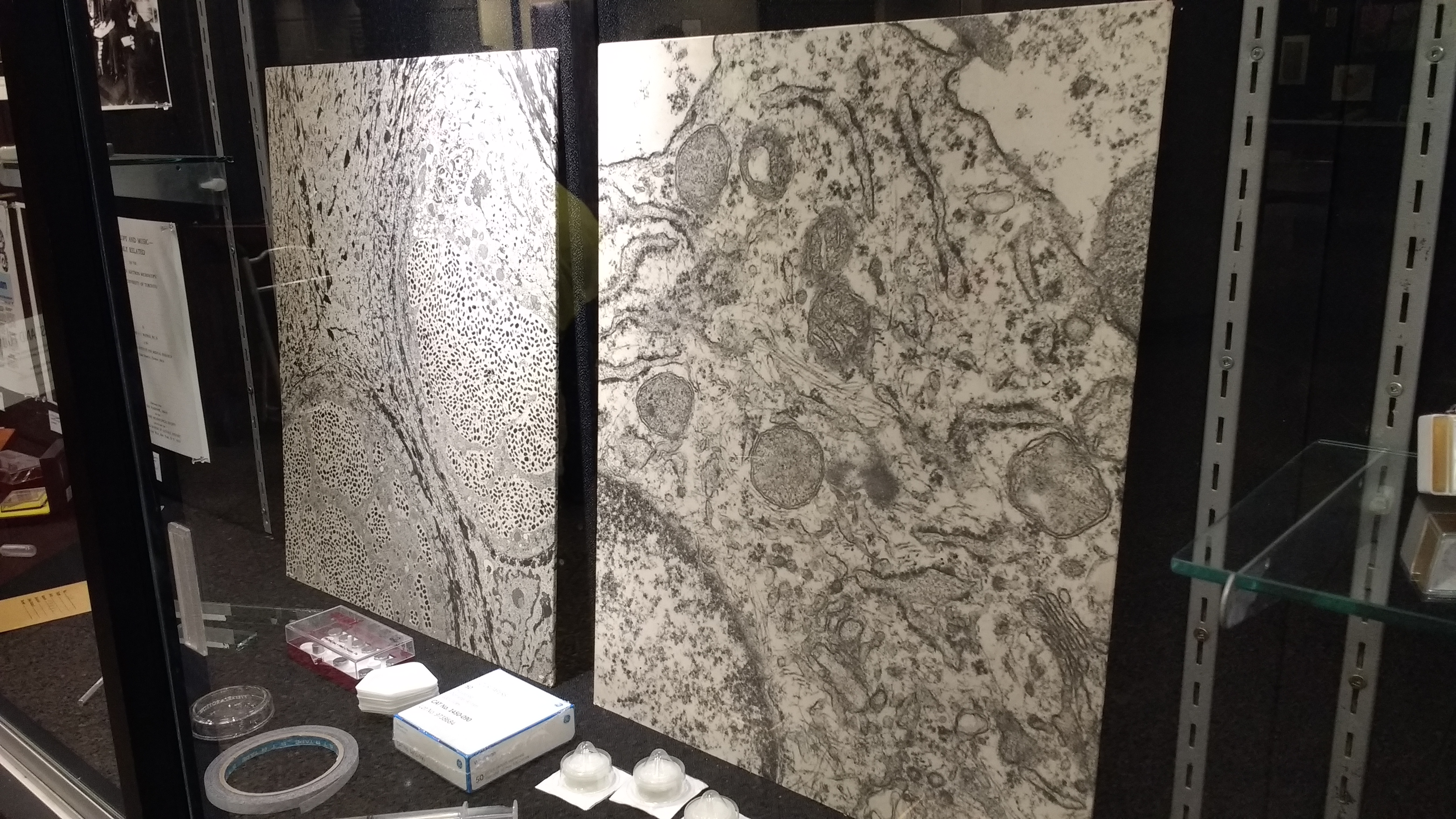

The electron microscope (EM) is used for everything from looking for fault lines in engine parts to determining protein structures. In addition to its myriad functions, this powerful tool also has an interesting story behind it. In her installation, “Seeing the Invisible: The First North American Electron Microscope“, award-winning Toronto-based artist Nina Czegledy displayed a cross-section of history. Her exhibit showcased photographs of the first EM to be built in North America, the “1938 Toronto model”, and the scientists who put it together. These historical images were complemented with books on electron microscopy (written by some of its early developers), tools used for sample preparation, and electron micrographs.

The first EM prototype was built in Germany by Ernst Ruska in 1933 and was based on his work with the engineer Maximillion Knoll. While ground-breaking, this design never surpassed the resolution achieved by light microscopes. Other European scientists refined this model enough to produce micrographs of biological specimens. The first North American EM, built by U of T graduate students Cecil Hall, Albert Prebus, and James Hillier, was the most practical model designed at the time and served as the basis for the first line of commercial electron microscopes produced in North America.

“This was quite a heroic effort,” says Czegledy. “I think that it is quite significant and remarkable that two graduate students in 1937 – they had very little financial support – created the first ever working microscope in North America.”

The initiative to build a transmission electron microscope (TEM) at the University of Toronto was driven by Eli F. Burton, who was the chair of the Physics Department at the time. Cecil Hall was the first to work on the project and built a simple TEM as a proof-of-concept. While this helped Burton gain support for the EM program, lack of funding caused Hall to leave. (He moved on to work for Kodak, and then to the Biology Department at MIT.) Prebus and Hillier picked up where Hall left off. Working over the 1937/38 Christmas break, they designed a more sophisticated EM. The microscope was built by a team working in shifts, with Prebus and Hillier working the night shift, often until 4 am. Following further tweaking during the spring and summer of 1938, their microscope’s resolution exceeded that of a light microscope and its images were of sufficient quality to be used in medical research.

Czegledy says that she was drawn to the Cabinet Project due to its “cross-disciplinary” and “intergenerational” nature. Her whole career revolves around the intersection between art and science. She started out in clinical biology and employed electron microscopy while working in the lab of Dr. Ernest Cutz at the Hospital for Sick Children. After this Czegledy “retrained”, as she puts it. She became a broadcast documentary filmmaker and then turned to creating media and video art. Currently, she collaborates with artists and scientists to organize touring exhibitions. When putting together her installation for the Cabinet Project, Czegledy returned to her roots and visited her old lab. “They were so kind,” she says, explaining how Cutz and lab members loaned her the tools, books, and maps used in the exhibit. “They came to the opening.”

Stories like this pose the question of whether there is a need for scientists to be more involved in art. “With the direction that education is taking now, it is inevitable that there will be more contact,” says Czegledy. “There are now more and more joint diplomas, and some of them are really intriguing.”

Nina Czegledy is a Senior Fellow at KMDI, University of Toronto, Adjunct Professor at Concordia University, Adjunct Professor at OCADU, Research Collaborator at Hexagram International Network for Research Creation, Senior Fellow, Intermedia, Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Honorary Fellow at Moholy Nagy University Budapest, and Chair of Intercreate, New Zealand. Czegledy is also a Board Member of AICA International Association of Art Critics Canada and a member of the Leonardo/ISAST Governing Board, contributing editor of the Leonardo Electronic Almanac and member of the Observatoire Leonardo des Arts et des Techno-Sciences scientific committee. Find out more about her work here and here.

To learn more about the first North American EM, see this early microscopist’s account of events.