Connell Lecture Series: Dr. Jeffrey Rothstein

Written by Kate Jiang

Dr. Jeffrey Rothstein is a Professor of Neurology at John Hopkins University and the Director of the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research. On March 27th, 2024, Dr. Rothstein was invited to give a Connell lecture about the role of nuclear pore complex proteins in neurodegenerative disease development. I had the opportunity to chat with Dr. Rothstein and learn about his scientific journey in both basic and clinical research, as well as his passion to bridge the two together.

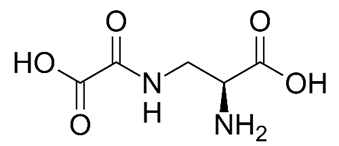

Dr. Rothstein did his MD/PhD at University of Illinois College of Medicine, where his PhD research focused on the roles of glutamate as a neurotransmitter. By the time he started his residency in neurology at John Hopkins Hospital, emerging evidence started to point to an environmental contributor of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). One such example is Guam disease, a neurodegenerative disease that resembles a combination of ALS/Parkinson/Alzheimer’s, which was found to be associated with a diet of false sago palm that contains high concentration of β-methylamino-L-alanine1. Another example was neurolathyrism, an upper motor neuron disease found in war prisoners during World War II, who were fed a diet of chickling pea that led to intoxication by oxalyldiaminopropionic acid2. Interestingly, both environmental toxins share structural similarity to glutamate.

From there, Dr. Rothstein saw a scientific opportunity to apply his PhD background in glutamate biology to gain a better understanding of ALS. Indeed, he found that the glutamate concentration in the cerebrospinal fluids of ALS patients is altered, suggesting an association between the two3. In addition, he was inspired by how scientifically oriented the neuromuscular medicine division at Hopkins was. “Many of the neurologists did bench science—they weren’t just purely clinical observers. I was enamored by my teachers, if you will, and the scientific opportunity of applying my past science of glutamate biology to ALS.” That eventually started him off on his journey in ALS research.

At Hopkins, Dr. Rothstein now has both a clinical team and a research team. The clinic team is led by a highly experienced nurse practitioner to whom he could defer some of the clinical responsibilities. On the research side, his lab consists of technicians, post-doctoral fellows and graduate students; he relies on the postdocs to mentor the graduate students in the early stages of experimental design. “If they (graduate students) said, ’Jeff, I have a problem developing this CRISPR reagent,’ yeah, I’m not the one who can help, but my postdocs can.” He emphasized that it is important to have a team of people one can trust, and that disease science is best done by teams.

Dr. Rothstein loved taking a collaborative approach in research, and enjoyed learning from each other and understanding how everyone could work together despite coming from different disciplines. With the help of philanthropic donations, he founded the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins in 2000, which was built with the idea of bringing basic scientists from diverse areas of expertise together. The funding process at the Packard Center is different from elsewhere in that the grant applications, evaluated by a science advisory board, are shorter than the standard applications; however, the projects are required to be collaborative, and the researchers are required to share their unpublished data at the Packard Center’s annual symposium. If the researchers are not willing to share their data, Dr. Rothstein would withdraw funding in the middle of the project. “If you’re not going to be part of a collaborative group, you shouldn’t be part of this group. Go somewhere else.” While that has occurred four times in the past 24 years, it has been a fantastic process, with hundreds of researchers having benefited from the funding. The last symposium took place in early March this year—a couple of weeks prior to Dr. Rothstein’s Connell lecture—with over 500 people attending in-person and online, collectively forming a community based not only on cutting-edge science but also on the sharing of data.

How would Dr. Rothstein define a good disease model? “No model is perfect. Period. No model is right. It’s the patient.” He still thinks the in vivo mouse model is valuable, as it has the connectivity of multiple cellular elements and is a readily accessible tool for scientists to study the disease, even if clinicians are not around. ALS mouse models have, however, failed to produce a reliable intervention in patients, despite his group having spent over 25 years working on them. Dr. Rothstein decided that instead of spending another 25 years on mice, he would rather gamble on a new model. His lab has since started using induced pluripotent stem cells, which allow them to gain new insights into human biology due to the cells having the stoichiometry and biochemistry of human proteins. He emphasized that the whole point of studying a disease model and pathway is to ask, “Can I intervene in patients?”. “You’re not doing [it] because you really care about curing a mouse. …When you do discover something in a model—I don’t care whether it’s a fish or fly—make sure that’s the same you see in patients. Now you have a better confidence in your observation.”

When I asked him about the meaning of life, Dr. Rothstein said, “I have not a clue. I deal with a disease that kills everyone.” Part of it is because he sees so much death, given that he works on a terminal disease. “I’ve got the highest mortality rate at John Hopkins.” However, he sees death in a positive way, as he gets to see families that are brought together by ALS. “The warmth of a son and daughter taking care of the mother—or an older [couple], I love older couples, some who’ve been married like 50, 60 years and watch the husband or the wife take care of one another. That’s pretty rewarding in some way.”

Dr. Rothstein leaves us with a piece of advice: “You got to pick something you really enjoy doing. … Science is not a 9 to 5 job. It’s longer than that. But really loving what you do is important.” Also make sure you work with people you enjoy working with, he emphasized. “You may pick a topic that’s great, but everyone around is an a**hole. You don’t want that either.”

You can find out more about Dr. Rothstein’s research at https://www.rothsteinlab.org/.

—

Reference:

- Spencer PS, Nunn PB, Hugon J, et al. Guam amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-parkinsonism-dementia linked to a plant excitant neurotoxin. Science. 1987;237(4814):517-522. doi:10.1126/science.3603037

- Cohn DF, Streifler M. Intoxication by the chickling pea (Lathyrus sativus): nervous system and skeletal findings. Arch Toxicol Suppl. 1983;6:190-193. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69083-9_33

- Rothstein JD, Tsai G, Kuncl RW, et al. Abnormal excitatory amino acid metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1990;28(1):18-25. doi:10.1002/ana.410280106