Stepping off the treadmill and into the park: A glimpse into the promising future of an alternative publishing platform

written by Claire MacMurray and Noel Garber

We have written the following article due to our firm belief in the need of a total reform of the publishing industry in the natural sciences. Once having emphasized the shortcomings of the model/industry, we will proceed to outline what a feasible and promising reform might (and hopefully will) entail. The shortcomings of the current publishing model will be revealed through metaphor. We invite you to read on…

Framing the problem

Let’s begin with an analogy by imagining that you are an avid jogger. You like to jog most days, perhaps a day off here and there, but it’s a regular habit— for good reason. Assumedly, you’ve chosen to run because it leaves you feeling exploratory, satisfied, engaged, etc. It is one component of a lifestyle that guarantees (or enables the pursuit of) health and well-being. What more could you ask for? If our first assumption is accurate, let’s go one step further by guessing that when given the choice between taking a jog on a treadmill or through a park, you are likely to choose the park. It is almost without question, yes? Then why, we beg of you to tell us, why have you confessed that you are enslaved to the treadmill, you can’t seem to break free—to visit the park right outside your door? The treadmill here represents the eternal publish-or-perish pressure we face to churn out neat little narratives as fast as we possibly can.

As everyone knows, the treadmill subjugates all other avid joggers. Everyone else seems to be running on the treadmill, and given their impressive musculature, it is all too convincing to feel as though you must choose the treadmill. But it breaks you down—distorts your priorities—and you are blinded to what exists beyond the treadmill, beyond the confinement of your gym. Thoughts of exploration, inquisition, and discovery no longer entertain your mind. It is impressive musculature that you desire— a metric of success. And of course, it is more than apparent that without the similar extent of musculature to those who surround you, one morning, there will be no treadmill for you to occupy. You will be cut-off— an absolute failure, without the means to accomplish your wish to jog. The land of the treadmill-joggers is cutthroat and you’ve got to do what it takes to survive. “What is this park bullshit?”, asks the man to your right with the bulging calf. And you begin to ask the same question of yourself. The walls of the gym have closed in on you. No longer can you escape…we are here today to reveal that this dismal metaphor is not the entirety of the story.

What have we learned from this slight parable? Perhaps we’ve failed in making things obvious, but the purpose of our musings is to remind all avid joggers that the park really does exist – to remind all scientists that there is an alternative to this treadmill-like culture of the current publishing model. To break free from the consumptive treadmill is more than feasible. Let’s be clear on the appeal of the park (and what it really means to be an “avid jogger”). You, as a practicing scientist (or a scientist in training), through the act of running, feel as though your efforts to practice science are being met. To run is to “perform science”. And when performed within the park, you notice things, many things—an absolute cornucopia of life and all its mysteries: the humongous lily pads that bear the most stunning of flora, the ducklings as they waddle without purpose, the budding greenery in the earliest moments of spring, the embrace of two lovers (what brings them so close— you ask yourself). The park is abundant and you are filled with intrigue. You’ve regained purpose. You are no longer running for the sake of proving your worth (and musculature) to others. You feel reawakened to a much purer form of running, perhaps as you once intended it to be, and you are no longer led astray by disillusion with treadmill-borne musculature. You no longer play the nasty game of doing what it takes to “succeed”—to bulge.

This little anecdote was sparked/inspired by a conversation with Dr. Alex Freeman— the founder/creator of Octopus, a revolutionary new platform for scientific publishing and the solution we endorse for the broken system of treadmill-running in a publish-or-perish culture. Octopus, which we will describe more thoroughly in the following section is the platform that will revolutionize science as we know it – Dr. Freeman beckons for you to “run through the park”.

To put things bluntly, science is an industry. Its currency is publication record – this is more than apparent. The more publications filed under one’s record, the better things prove to be (i.e. you’ve got a better chance at securing a job, grant funding, etc.). With emphasis, we ask you to consider the following: what type of scientific work— of material—is getting published? In Dr. Freeman’s mind the answer is straightforward: a predetermined, digestible, linear narrative. Published narratives, I specify, are not reflective of the truth per se (i.e. the messiness of the scientific endeavor, of running through the weeds along the meandering path). They read nicely, yes, because they give off the illusion of science unfolding unidirectionally and without any sort of encountered hiccup/detour. Students are taught to “lead with a narrative”— to imagine what will get published and design an experimental platform based on this. Leading with a narrative completely biases one’s perception. The task of the trainee (as things stand now) is to perform just the “right” experiments such that a publishable bundle of work is produced, and consequently (once having acquired enough data to see the narrative to completion), one’s likelihood of surviving in the cutthroat world of academia is strengthened.

What of this work-flow is reflective of science as it was once/originally perceived? Where lies the art of the experiment, the uncertainty that must be welcomed and appropriated, the messiness, the pluralism, the continual veering of left and right, the intent to falsify rather than prove or demonstrate? It’s precisely the “leading with a narrative” mindset that skews the progression of science. The scientist becomes blind to what sits outside of the narrative. To perform science to publish for one’s own sake (rather than to explore, to inspire, to collaborate, to explain, to understand) is to fall subject to the demands of treadmill culture. But again, Freeman (the founder of Octopus) is here to direct us to the park.

An alternative publishing model

Octopus is a platform that begins to address these critical issues by allowing researchers to instantly publish small units of research that can then be publicly reviewed and rated by peers. The current scientific publishing model incentivizes researchers to withhold data, sometimes for years, until it can be fit into the context of a ‘story’ or narrative which has been termed the “minimum publishable unit”. In Octopus, scientists can publish data as it is generated and analyses of data as they are performed, empowering the broader research community to know what has been done.

“It really struck me when I came back to academia from working in the media that academics were being assessed on the same criteria: how good they were at telling popular stories. And good stories are not the same as good science.”, says Dr. Alexandra Freeman, the creator of Octopus and Executive Director of the Winton Centre at Cambridge, when we met with her to discuss this new platform. “Octopus is designed to […] be the primary research record: the place where all work is recorded in detail and in full and time-stamped”. In contrast, Freeman argues, this frees journals to serve to “aggregate and disseminate the latest findings to those who might put them into practice, or discuss topical and controversial issues in a field”.

There is a major benefit to us as graduate students to publish primary research data in Octopus in real time as our research progresses. We live under the constant risk that our work will be ‘scooped’, meaning that it is published first by another group that made the same discovery, but this is an artificial problem produced by the current model of withholding data until it fits into an article. In Octopus, however, the problem is largely solved by allowing instant ongoing [ real time ] publication – once data is collected and immediately published, it is not possible for it to be ‘scooped’ thereafter, because it is already “out there”. This totally transforms the scientific process as we know it.

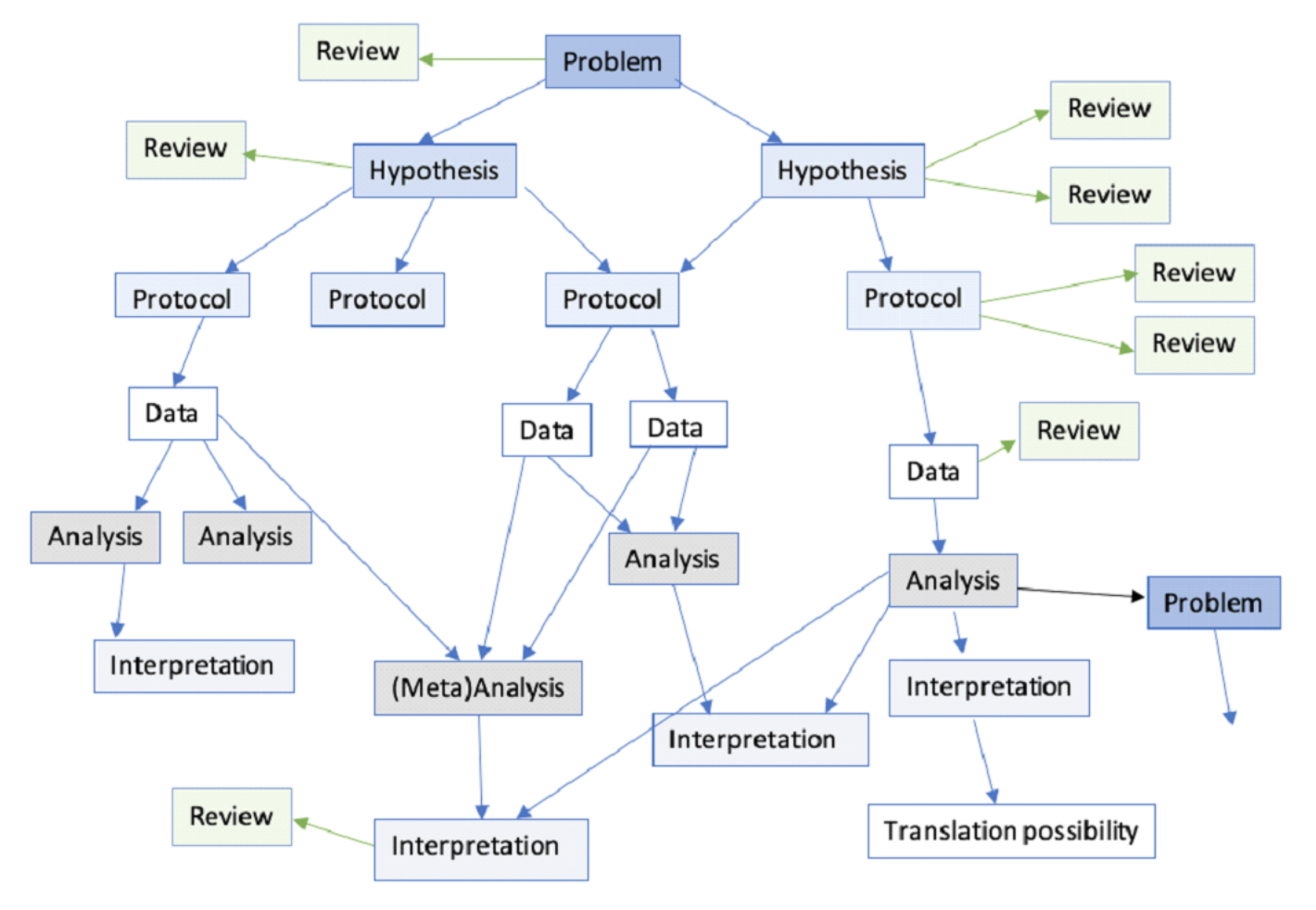

Publications are stratified under 8 subtypes in Octopus. Scientific problems, which encompass overarching research questions, are initially defined concisely on their own. They comprise the first type of publication to which all other types are linked (see diagram for publishing flow overview). This is followed by specific hypotheses and theoretical rationales regarding the defined problem and comprise the second type. These are published before the data, allowing researchers to be credited with logical ideas regardless of experimental outcomes. Even in the case where a published hypothesis leads another researcher to collect and publish supporting data, the original author of the hypothesis receives significant credit because the idea is theirs. This is radically different from the current state of requiring positive data before a hypothesis or rationale can ever be aired and critiqued.

Work in the laboratory is published under two subsequent types – methods and protocols, or data and results. In a methods/protocols entry, a laboratory procedure is described in detail, along with a description of how it can be applied to one or more hypotheses. Conversely, in a data entry, the outcome of the work is published; this is again in small units, published as it is collected. For an example of the need for this kind of instant and ongoing publication, we need only look to the current COVID-19 crisis, in which researchers must turn to preprint servers to avoid an otherwise unacceptable lag in publication for information we need now. But even this is not a complete solution, because preprints still require neat and clean narratives that take too long to fit ongoing research into before getting it ‘out there’. Moreover, ongoing efforts become transparent to the scientific community which in turn minimizes unnecessary duplication of research.

Methods and/or associated results can be published before subsequent analyses are performed, as analysis represents the fifth type of entry and is published separately with links to the results they reference. This also allows unbiased secondary analysis from independent third parties, which will either strengthen the primary analysis by the authors of the results or offer an alternative. Once analyses are performed and published, interpretations of those analyses comprise the sixth type of publication and can again be published by the results/analyses authors and/or third party authors to relate back to the initially defined problem.

Translations, new applications of existing methods of data collection and analysis, are also publishable by third parties, encouraging an interdisciplinary approach where diverse fields of science can draw from one another. If one were to find a novel application for a technique used in another field to their own research, both the original developer of that technique and the third party that translates it to a new application receive credit for their work. As a recent example of the benefits of this kind of interdisciplinary thinking, the CRISPR gene editing system was developed by taking one system discovered in microbiology and applying it to a completely different area in mammalian cells. Hence, we note our ever increasing need to draw on parallel fields outside of our ‘research silo’ in order to further our work.

The eighth and final type of publication in Octopus is the review, which is analogous to the existing conception of review articles in journals. Its purpose is to review all of the other types of publication for a specific problem and define major themes, evidence, and outstanding questions. By allowing open and unbiased reviews from multiple third parties who all receive equal credit, we can get a more holistic view of the state of current knowledge for any particular problem or set of problems.

If we as an academic community shift our practice to publish data as we collect it, this will empower the field to work with current information and design experiments more effectively based on that current information. It will allow different labs in the same field to complement each other’s work on an ongoing basis instead of having to compete to publish a narrative first. Our current publication system is broken – it forces us to cut corners and rush to fit our work into neatly packaged narratives, and that makes for bad science (if it even can be called science?), perhaps even contributing to the reproducibility crisis that has taken centre stage in recent years. However, we as the next generation of scientists have a real opportunity for transformative change to address these critical issues, and we argue that this starts with Octopus.

As things stand, we as trainees and young scientists are runners on a treadmill of eternal struggle to publish as many neat little narratives as humanly possible. We have forgotten that there is a park, that there is a greater purpose to the scientific process. Octopus functionally reminds us of this fact and re-enables open and collaborative science to take place in an ongoing and ever-growing manner, and it is slated to come online this autumn in 2020. We ask that you do everything you can to normalize this new and exciting approach, visualize what it can do for your work and interests, and promote it to your colleagues and principal investigators. An exciting new future for open science lies ahead, and the time to act is now.